![[Belladonna]](../jpeg/belladonnapretty.jpg)

Products: Belladonna Turntable and Septum Pick-up Arm

Manufacturer: Audiomeca - France

Cost, approx: Belladonna 15000 Euro, Septum 5000 Euro

Reviewer: Geoff Husband - TNT France

Reviewed: February, 2007

![[Belladonna]](../jpeg/belladonnapretty.jpg)

The introduction to this series of three articles can be found in "Part 1", but now we get to the "nitty-gritty". For this article I will be looking at the design of Belladonna and the principles behind it. The Septum arm will come in Part 3 in three weeks time, and obviously some of the theory explained in this article will be applicable there and visa-versa. I'd also point readers to my review of the Audiomeca Romance and Pierre Lurne's interview on TNT where some of the principles involved have already been explained - I apologise in advance for any repetition. It's also interesting as the Romance was designed as a mid-price unit and the compromises involved in the design make an interesting comparison with Belladonna, which is a cost-no-object design. Lastly I flagged this article as being in-depth, but having reviewed all the literature Pierre supplied, I realise I am only scratching the surface of the design, but at well over 5000 words it's already a very long article...

Pierre Lurne is an engineer and physicist whose whole life has been taken up with designing audio products and in particular turntables and arms. Thus his designs are based on measurable, repeatable and demonstrable physical properties. There are several commercially successful designs, often based on older designs, where the impression is that the turntable has been built by an enthusiastic amateur who has spent a great deal of time tuning by ear - in effect they have treated the process as an art, not a science. Quite a few I could mention seem to have been designed to be an "objet d'art" first and foremost :-) Pierre is the first to acknowledge that even his designs have their fair share of art and fairy dust, but that they are grounded in Physics. As he says, "sometimes I look at another design, and though it might sound wonderful I believe it would sound even better if the physics were correct."

This is why following the gestation of Belladonna has been so fascinating for me, as each stage has a logical explanation. Once again, though Pierre will insist that in most cases his way is the only correct way, I am not in a position to confirm or deny that assertion and am open to other equally well explained alternatives should any be presented to me.

Although there are many design features of Belladonna, in order to understand the whole we need to understand two basic principles.

Here you are going to have to forgive the ex-science teacher left in me - this is me moaning, not Pierre Lurne. Few things annoy me as much as PR claims which simply deny the most basic of scientific laws and one of my bete-noires is the Conservation of Energy. This is a LAW. You cannot destroy energy. It can be transformed into another form of energy, so electrical energy can be transformed to heat, light, mechanical (via a motor), radio, sound and so on. The total amount of energy remains the same.

Here's a typical line from a PR sheet for a speaker. "All back radiation from the driver is absorbed". What the hell does that mean? The implication is that the back radiation just "goes away". It's total PR speak. Inevitably shed loads of vibrations come from the back of the driver - it may be that some clever stuffing takes that energy and converts some of it to heat, or may "damp" it, spreading the frequency of vibration over a wider range so reducing peaks, or the cabinet will be tuned to certain frequencies less damaging to the sound, but the total amount of energy in the system will remain the same until it is radiated as heat, vibrations whatever, to the outside. It is impossible for energy to "disappear" within the speaker.

How does this relate to turntables? Well one of the fundamentals of their design is the control of vibrations - what happens to all that energy? We'll explore this when we get to the design of Belladonna

Pure Mass is a well-established physical concept, Pierre is at pains to point out that it is not his invention but rather a physical law, long established, but it is one largely ignored by turntable manufacturers. Pierre Lurne has been championing this for over 40 years and knows it brings huge benefits to turntables.

A body can be said to be a Pure Mass if it is perfectly balanced around a Point of Rotation, which is also the Centre of Gravity. If a force is applied to such a body, it moves in response to that force in the simplest way, not through a couple ( force x distance). It requires the same force to move a given distance in all planes of movement, not more force to move left, or up-and-down, no swinging back and forth to a preferred position like a pendulum. The body has no will of it's own, no character - it reacts perfectly to any input of energy.

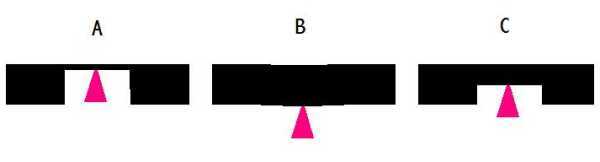

Here you see three bodies supported by a point/bearing. My limited drawing shows them in 2-D but if you imagine each as a fat disc then you get the idea i.e. they make nice analogues for a turntable platter. Diagram A has the Centre of Rotation (where the point is) at the centre of the disc well above the Centre of Gravity. It is stable until there is any energy input. If you tilt the disc it will swing back and forth until the disc returns to level with the Centre of Gravity once more below the pivot. Thus the body has a "resonance" frequency - if energy in the form of vibration (or a simple push) is put into this system, some of the energy will provoke this swinging motion. If this swinging is combined with other movements, for example rotation (now you see the importance), then the interaction is immensely complex/chaotic and difficult to predict with all sorts of resonance all over the place, call them "wobbles" if you like. It is not a Pure Mass.

Diagram B shows a similar body where the Centre of Gravity is well above the point/Centre of Rotation. This situation is unstable and the disc will simply fall over. However add any other motion such as spinning and again the result can be chaotic. A good example of this is a child's spinning top. Spinning rapidly it appears to be in balance, held by the gyroscopic effect. As it slows its movements become increasingly chaotic until it falls over. The mixed forces coupled with the inevitable imbalances in construction make it wobble rather than just stop and then fall over. It is not a Pure Mass.

Diagram C shows a similar disc where the Centre of Gravity and Centre of Rotation are coincident. If you tilt the disc it simply remains tilted. It doesn't swing back and forth, it doesn't have a resonance of its own. It has no character. If you then caused the disc to spin it would simply spin in that attitude, it would not go into complex wobbles like A or B. In effect the "platter" is quite content to spin naturally and nothing else - it doesn't try to translate that motion into any other movement. If you could build a top with such a geometry it would simply slow to a stop with no wobbles. This is a pure mass

The most obvious application of Pure Mass is to be seen in the design of Belladonna's platter and main bearing, a design which in simplified form was used by the Romance turntable, and very similar to that used in Pierre's earlier high-end designs, the J1 and J4.

In most high-end turntables the platter is supported by a bearing point at the end of a long shaft sticking below the platter. For example I have here a turntable which has a massive 15kg platter where the bearing shaft extends 8 cm below the platter and nearer 12 cm below the centre of gravity. Obviously all weight of the platter and bearing is born on the point of that bearing. In effect we have an extreme case of B above. Imagine balancing that platter by putting the end of that bearing on a tabletop and trying to hold it upright by gripping the bearing shaft. The falling moment will be huge and you've no chance! The platter will begin to tip and then just accelerate to crush your hand. Now that is exactly what bearing sleeve will be trying to stop - keeping that highly unstable platter from falling. The tiniest error in levelling, imbalance in the platter or the pulling to one side by a drive belt will put great pressure on that bearing sleeve. It will also have a tendency to chaotic movement like the slowing top in example A. Therefore the bearing sleeve must be a massive affair, very tight fitting and with a big contact area.

Belladonna's bearing couldn't be more different. The platter is high-mass, 10 kgs, (total inertia of 2 tons), but because the platter is perfectly balanced and the bearing point/Centre of Rotation (a tiny tungsten ball) coincident with the Centre of Gravity (example C), the bearing sleeve has practically nothing to do. You could tilt the whole turntable to 45 degrees and still the platter would not exert any force on that sleeve. In effect the sleeve is only there as a "keeper" otherwise cueing a record would cause the platter to tilt. In effect the only load-bearing part of the bearing assembly is the ball itself. With such little force applied to the sleeve by the platter, the sleeve can be made of a low resonance material, and have only a small contact area. In the case of Belladonna the sleeve is a simple ring of Delrin. This also means that the bearing, geometry is defined by just two points, the ball and the Delrin ring.

On all other bearings I've seen, a tightly fitted sleeve touches all the way down the shaft. Except it doesn't - at a microscopic level the bearing sleeve will touch at various points (though through a film of oil) which will vary as the bearing rotates - one second the geometry will be between the bearing point and the sleeve touching 4 cms below, then 2 then 5 etc etc. At the very least the bearing will have three points of reference, the point, the top of the sleeve and the bottom. Thus the bearing will have at lease two different axis rather than the one that Belladonna has. Does this have an effect? Does it give a whole series of constantly changing resonances within the bearing, different paths for vibration to escape? Is this significant or purely academic?

But what incontrovertible advantage does the Lurne arrangement bring? Spinning the platter by hand up to 33 rpm (belt removed, speed checked by a strobe) and releasing it gives a run down time of about 25 seconds for the aforementioned turntable, Belladonna's bearing took over 4 minutes*. Given that the former has a heavier platter with inertia of 3 tons, the friction must be an order of magnitude greater than that for Belladonna. To keep the platter running the motor must provide more energy, and all things being equal the greater the load on the motor the noisier it is.

And here we get into conservation of energy. If the motor is drawing more electrical energy in order to drive the platter, then that energy is all being pumped into the system and must go somewhere. Where does it go? It is converted by friction into heat, and vibration/noise, and both are going to be greater in such a high-friction bearing than Belladonna's. The danger is that in order to sink more vibration and heat, the designer then engineers an even bigger, more impressive bearing...

So you see that here, the correct application of Pure Mass has brought various benefits, less motor noise, less bearing noise, lower wear rates, reduced significance of critical levelling, no complex resonance and so on. It's also easy to balance the platter to near perfection, as by balancing the platter without the Delrin ring, any imbalance is obvious as it tilts the platter.

Pierre Lurne insists that this is the only correct way to make a platter/bearing i.e. Centre of Gravity and Rotation coincident using an inverted bearing. In fact he's quite baffled (read "irritated"...) as to why 30 years after the idea was widely dissimulated in the press, people still make them "wrong". Some turntables using inverted bearings throw these advantages away by being either like example A or B - i.e. having the bearing away from the Centre of Gravity or insisting on coupling them with massive bearing assemblies. Perhaps they feel the public is more impressed by lumps of brass than a sliver of Delrin? For those worrying about the longevity of such designs remember that Lurne turntables have been spinning like this for 40 years.

As mentioned before this is the standard pattern for a Lurne turntable, but with Belladonna he has extended the Pure Mass concept to all parts of the turntable.

Conventional turntables mount their main bearing in one of two ways. First they can be fixed to a subchassis, which in turn is suspended (or supported) on springs/elastic in order to isolate the working parts of the turntable from the outside world. These springs are tuned to certain frequencies (usually 1-5Hz to avoid being excited by record warps) and energy from platter/motor system that is not managed by the subchassis can be transformed into low frequency vertical movement where it will do least damage to the sound. This is why the setting-up of suspended turntables is such a black art - as anything but a perfect vertical bounce will provoke all kinds of parasitic movements (wobbles again) which again are uncontrolled and chaotic and can reach well into the audio spectrum. Anyone who has spent a jolly afternoon trying to get an LP12 to bounce cleanly will sympathise.

The snag with almost all such designs is that no matter how well set up there will always be some parasitic movements, poor mass distribution, non-standard arms with different weights, tired springs, odd springs and just bad design make things worse. When you add the sideways pulling of the motor on such a system you can see what a nightmare it is to get right.

The other option, and one increasingly popular, is to use a solid plinth. This is a misnomer as most of these designs have complex layering and shaping (if they are any good) in order to damp and manage vibrations that come into them. Well designed, they can be very effective (as can suspended turntables), but too many just substitute mass for science.

I've been simplistic here, there are many variations and half-way-houses amongst the plethora of different designs out there, but 99% of turntables will fall somewhere in those two categories, Belladonna doesn't and forms a new category of her own...

Pierre Lurne's approach is radically different. When he first described his idea to me I couldn't see how it would work but it does :-)

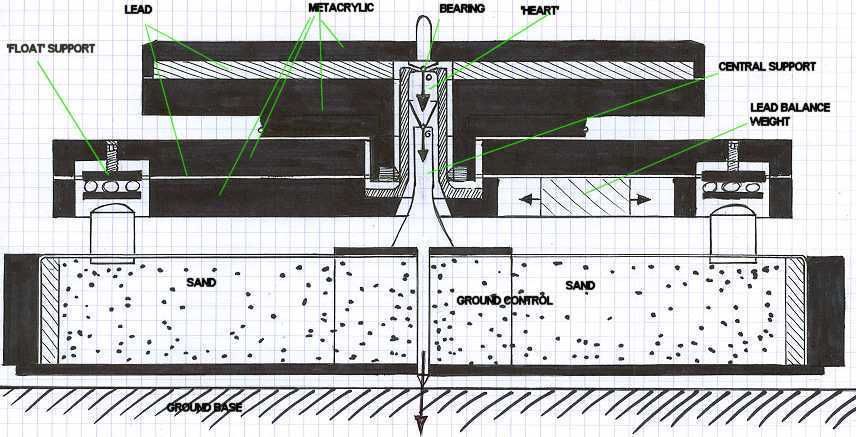

Explaining how this all fits together is a nightmare, but Pierre has supplied the following drawing for us so the text refers to that.

In Belladonna the subchassis, which supports the arm and platter/bearing, is also balanced on a single point which is the Centre of Gravity/Centre of Rotation for the combination - combined with the platter/arm and armboard it is a Pure Mass too! You could almost see it as a Lurne platter with another, bigger Lurne platter underneath...

The secret to the design is the "Heart of Gold". This is a small, bullet shaped (and sized) piece of hardened steel - the flatter end of it forms the bearing surface for the tungsten ball bearing, which sits in a tiny cup, below it is the point of the "bullet" which sits on another bearing cup. This takes the weight of the platter/subchassis/arm and allows the whole assemble to rock in any direction. After a lot of experiments and listening, this pure design gained a small compromise in that it was found that a second spike under the arm, taking about 10% of the total mass, made for a better sound. This presumably because there was then a second, direct drain for vibrations from the arm. It also made set-up very simple, as the subchassis only had to be balanced in one direction by moving a large lead weight - a simple Allen key adjustment that takes 30 seconds. To stop the subchassis overbalancing there are two "Floats", these are adjusted (and adjustable) so they just touch supports on the GC and take no weight at all. In fact the subchassis will balance without these so they are merely "keepers" and so transmit practically no energy.

This still leaves the subchassis/platter/arm as a near Pure Mass, with the same advantage that the platter/mainbearing has, i.e. no parasitic movements, but the design has other significant characteristics.

Looking at Belladonna, it is almost as if the platter/subchassis is a solid plinth design. The subchassis is made of two thick layers of Metacrylate with a slice of lead sandwiched between, a similar structure to the platter - though the platter has a thicker lead layer. The thickness' of the layers are calculated in much the same way as room acoustics. We're all familiar with standing waves in a room and how some dimensions and ratios reduce standing waves and spread them more evenly. The same applies in solid masses, Belladonna's layers are doing the same thing. I suspect that simply siting the subchassis on a table support would add up to a pretty good solid plinth turntable :-)

But the next layer that goes to making up Belladonna is the plinth or "Ground Control" (GC). This is the biggest part of Belladonna and the heaviest, at 500mm x 460 mm and over 50kgs total it's a big turntable. Rising out of this plinth are two vertical structures, the central one is tapered to the top and supports the "Heart of Gold", the other is smaller and supports the downward facing spike from the armboard.

The box of the GC is made of Metacrylate, the top is black leather (yes it is all rather pornographic) and the inside is full of sand. Anyone who's made a TNT Sandblaster knows how effective sand is in damping vibrations, but here Belladonna has not only sand, but those two supports continue down through the sand to be fixed to the base (Metacrylate again).

What all this adds up to, slabs of Metacrylate, the subchassis balanced on two points, and the supports going through sand, is vibration control.

A turntable is simply a mechanism for turning mechanical energy into electrical energy. The mechanical energy is supplied by the turning of the platter by a motor and the conversion occurs when the stylus wiggling in the record groove moves coils or magnets in the cartridge and produces an electrical current. Any movements at the stylus which are not directly related to the music signal will also be converted to electrical energy, but as they are not on the record they are bad vibes - i.e. noise.

The process of spinning that platter inevitably inputs far more energy into the system than that converted by the stylus as music, so the remainder must go somewhere. The last thing we need it is for it to add to the music, so somehow it needs to be kept away from the stylus. Some of this will be covered in Part 3 when we get to arm design, but for the moment I'll concentrate on what the turntable is doing.

We've already seen that a lot of energy goes into the main bearing itself, and here is converted into heat and vibration. The Lurne bearing already minimises both, and reduces the amount of energy the motor needs to supply, but what noise is produced in the bearing has a direct, hard path through the "Heart of Gold" down though the central pillar and into the sand of the GC. This easy, path-of-least-resistance, siphons vibrations down. Sand is brilliant at handling this sort of energy because each grain takes some of the vibration and converts it into heat by the friction of the sand grains rubbing together. The high mass and large surface of the sand makes this doubly effective. Very little of the vibration entering this sand will bounce back up towards the platter - the tapered shape of the support further reducing this.

But of course where two solids touch there is the potential for vibrations to be passed on. The main bearing is in contact with the platter and so some vibration will enter here. In addition the record itself will vibrate in sympathy with the stylus. The platter layer in contact with the record is Metacrylate, which is very similar to vinyl and allows vibrations to cross the gap from disc to platter as easily as possible - helped by the record being clamped hard onto the surface. Once in that thick layer of Metacrylate the vibrations bounce around but before bouncing back to the record they encounter the layer of lead. Lead is a "Magic" material. It has very High Mass and good damping factor - it is soft and has a very slow speed of sound, around 1/5 of that in steel, no other metal comes remotely close. At an atomic level it acts very like the sand in the GC so vibrations are converted to heat, (of all metals lead makes the worse bells). Very little will bounce back to the record. We'll go into this in greater detail in Part 3, but lead is to be found in almost all, current, high-end turntables and with good reason. Likewise any rogue vibrations from the main bearing, and from the motor via the rubber drive belt will be dealt with by the platter, or be funnelled down through the Heart of Gold and to Ground Control.

The Heart of Gold is also in contact with the subchassis, as is the pick-up arm. The latter has its own drain to Ground Control, but inevitably some vibrations enter the subchassis. The construction of the subchassis is almost identical to the platter and it too is well able to control vibrations by converting them to heat internally, or sinking them direct to the Ground Control.

All this would seem to be enough, but there will still be some vibrations in the system, and as a final solution Belladonna has a purpose built stand - The Ground Base. At the centre of the base of GC there is a downward facing spike, directly connected via the Heart of Gold to the mainbearing and platter. One hard, direct line passes through two massive sandwiches of Metacrylate and lead, then through a thick layer of sand, all reducing the vibrations - what's left goes through this final spike into the granite top shelf of the Ground Base. The Ground Base also helps isolate the turntable from outside vibrations, but those reaching the turntable are dealt with much as those generated by the turntable itself.

This final layer of vibration control uses the same principle as TNT's "Flexy" equipment rack, though far more complex. The rack is extremely rigid in the vertical plane, but can rock horizontally at a frequency around 1 Hz, well below music signal or warps. To "guild the lily" you can even sand fill it, but check the joists of your floor first!

All this might seem like overkill, but when you consider that the grooves cut in a disc are at the limit of resolution of an electron microscope, you can see that any vibration other than the music signal that gets to the stylus will have huge detrimental effects. This freedom from bad vibes is difficult and thus expensive to achieve, which is one reason high-end turntables cost a King's ransom.

Not content with reinventing the turntable, Lurne also wanted to improve on the drive system used in most modern turntables.

Because of its low friction bearing, we know that the motor will have to do less work, and so it will pump less energy (including vibration) into the system. In effect instead of having to constantly drive the platter, the motor is just giving the tiniest top-up. To aid this Belladonna has a split-phase power-supply designed by ABC PCB (formerly Anagram) to provide a perfect sine wave to the low voltage AC motor. Speed is adjustable, but as this is an AC motor, once set it will not drift. I know there are arguments against AC motors, that they cog, have vibration at 50 Hz and so on, but this AC motor is seems silky smooth (I couldn't feel any vibrations) and the convenience of not having to faff about with potentiometers to get speed right is a boon. The power supply also allows you to adjust the current to the motor so that you can reduce it so that it is just enough and no more - again minimising vibration. But once set you never need touch it again - a far cry from adjustable DC motors/supplies I've had here which need daily checking. This power supply is buried deep in the sand of the GC and so the chance of significant vibrations coming from the power supply is slim - buttons on the edge of the GC control speed, either 33 1/3 or 45 rpm.

Given that Belladonna has been designed from the outset to be a cost-no-object design, Pierre was still not satisfied that the motor system was as good as it could be. So the motor was mounted in a 3 kg lead block - the reasons for this you'll be familiar with. Then the motor itself was modified with flywheels fitted above and below the rotor. The effect is to further smooth the running of the motor, to place the Centre of Gravity of the motor at the physical centre and to add an immediate store of energy in addition to the heavy platter - without resorting to an overly powerful (and thus noisy) motor, or separate flywheel with its extra, potentially noisy bearing.

Then this motor assembly is mounted in a unique way. Normally motors are rigidly fixed, the snag being that this means that if the drag on the belt increases the load on the motor will also increase, which will either slow it (if it were a DC motor), cause it to cog, or increase vibration, or make the belt stretch and then bounce (chaotically). To my knowledge only one company have attempted to address this problem, and that is Roksan. They mount their motor on a sprung pivot, which allows it to move towards the platter when drag increases, thus keeping the load on the motor and thus belt tension constant. In Belladonna the solution is ridiculously elegant. The motor block is supported at two points only - without the belt it falls over, away from the platter. With the belt fitted the motor leans back against the belt like a fat man on a massage machine :-) If the load increases the motor can move fractionally forward to balance things again. These points sit on two supports which in turn sit on an "island" on the sand of the GC - the only link between the subchassis and the motor are those two points, the belt and a layer of sand. This almost totally isolates the motor from the platter, and is much less hit-and-miss that an offboard motor which is reliant on the support itself for isolation. Some designs place the motor a long way from the platter, in theory this allows the motor to sit on a different support to the turntable and so be well isolated. The downside is that the further the motor the tighter the belt needs to be - depending on belt construction that can increase transmission of vibrations or end up with resonances in the belt. The pulley of Belladonna is hard up against the platter and the belt relatively slack.

As I said at the beginning I'm just scratching the surface of the design, Belladonna is full of little design details, sometimes included simply because "if it's easy to make it right why make it wrong?" One example being the underside of the platter. When designing the CD mechanism for his range of CD players, Pierre found that if the platter was made aerodynamic it reduced pulsing pressure waves around it. OK, a CD rotates at 500 rpm, but as it was no more difficult to make a platter where the underside had a slight taper to reduce this effect then why not do it? So Belladonna has an aerodynamic platter!

Reading the above it would seem that Belladonna is hideously complex and the natural assumption is that it will need an expert to set it up. In fact it slots together in a very simple manner. I managed it from scratch in two hours without a build manual - always a good test, and that includes assembling the Ground Base. Compared to most turntables it's a doddle. Most things are pre-set at the factory, but equally there is huge potential for tweaking - let's face it, most of us love fiddling... The balance of the subchassis is altered using a simple Allen key adjustment to move a heavy lead weight underneath. The amount of pressure on the "floats" adjustable from above. The motor position can be altered by Allen key, motor power is variable and of course the Septum Arm is as adjustable as any.

"Form follows function"* - As I've already said I'm biased, but I think Belladonna looks striking and beautiful, you may hate it. Acres of black Metacrylate help of course (but photograph badly!), but chosen primarily because of its similarity to vinyl and the fact that it doesn't ring. But when you look at her carefully there is not one single part that is anything other than functional - not one piece of embellishment or decoration beyond the gold "Audiomeca" on the front, and you can always leave that off... If you are looking for "bling" look elsewhere.

I've promised not to review the sound qualities of Belladonna, but I think a general comment on its characteristics is useful. Judging by the prototype the design is not one of those "stripped-bare, images frozen in space, information-first" designs. It also lacks obvious colouration. It is big, bold and dynamic. The one thing it does which took me utterly by surprise is the ability to cleanly pull the lowest possible notes off vinyl. My fillings are still loose...

Phew! A long, complex article but I hope most of you have been able to follow my ramblings as in three weeks time we get to see how Pierre's other baby - the Septum arm - is put together...

*This is on the prototype where the bearing is not to the full production standard, having been machined and hardened as a one-off. No turntable I've tried comes close to this, the best being the Orbe with a time of just under 2 minutes - the Orbe uses an inverted bearing but it is of the "massive" variety. My own Opera "Droplet" likewise has a massive inverted bearing with a run-down time of 20 seconds...

*Frank Lloyd Wright - though Garrison Keeler insists he said "Function follows Form" but his wife corrected him...

© Copyright 2007 Geoff Husband - www.tnt-audio.com